Bike reviews often spill a fair amount of ink detailing a particular model’s geometry. In the past several seasons, particularly, manufacturers have been creating trail bikes that are lower, longer, and slacker (LLS) than previous generations. It seemed for awhile that it was a game of oneupmanship, where companies wanted to be able to say that they had the slackest bike available. In the more recent past, the LLS arms race has seemed to cool down.

For the purposes of this discussion, I will only cover 27.5″ and 29″ full-suspension trail bikes. Why not include plus bikes? Well, the majority of plus bikes currently on the market share the same frame as a 29″ bike and have similar – although not identical – geometry. Also, to keep the list from becoming too lengthy, I am drawing cutoffs at 150mm and 140mm of rear suspension travel for 27.5″- and 29″-wheeled bikes, respectively. My reasoning is that beyond these amounts of rear travel, you are really starting to get into all-mountain or enduro territory, which is another class of bike. It’s not a perfect definition as there will always be bikes that blur the categories, but hey, I’ve got to the draw the line somewhere.

In the rest of this article, I will cover the similarities and differences in geometry between trail bikes from major manufacturers. Of course, there will be outliers – like Nicolai – and custom manufacturers, so just go ahead and save those, “Why didn’t you include INSERT RANDOM BIKE in this comparison!?!?” comments. I want to instead focus on bikes that are widely available.

First, though, let’s start with a quick primer of the terms that will be used in this article.

- Head tube angle (HTA) – the angle, in degrees, of the head tube relative to the ground. Generally speaking, the steeper the angle is (closer to 90 degrees), the faster the bike will respond to steering inputs. A steep HTA also aids in climbing, as the front wheel will track straighter. A slack HTA puts the front wheel farther out in front of the bike, slows steering input, lengthens the wheelbase, and increases descending confidence.

- Effective top tube length (ETT) – the horizontal distance, measured parallel to the ground, between the center of the head tube and where it intersects the seat tube or seat post. As you go up in frame size, this distance will get longer.

- Seat tube angle – similar to HTA, except this is the angle that the seat tube forms relative to the ground. A steeper seat tube angle brings the rider’s hips forward, over the bottom bracket. A slacker angle will move the rider’s weight back over the rear wheel. This angle also has an effect on the ETT: a steeper angle creates a shorter ETT measurement, while a slacker seat tube will lengthen it.

- Reach – this is the horizontal distance between the center of the head tube and a perpendicular line drawn through the center of the bottom bracket. More and more, brands focus on the reach figure since it gives the rider an idea of how the bike will fit when standing.

- Stack – this is the vertical distance between the top of the head tube and the bottom bracket. Stack is important because it will impact how high or low your handlebars will be.

- Chainstay length – sometimes also called rear center, this is the horizontal measurement from the center of the bottom bracket to the center of the rear axle. Short chainstays are very much en vogue right now, as they can add a playful characteristic to a bike. However, short chainstays can also detract from high speed stability.

- Bottom bracket (BB) height – the vertical distance from the ground to the center of the bottom bracket. A lower BB height will aid in cornering, but also increases the chance of pedal strikes.

- Wheelbase – the horizontal distance between the front and rear axles. A longer wheelbase will increase high speed stability, and a shorter wheelbase will make the bike more maneuverable on tight trails.

And now, on to the bikes!

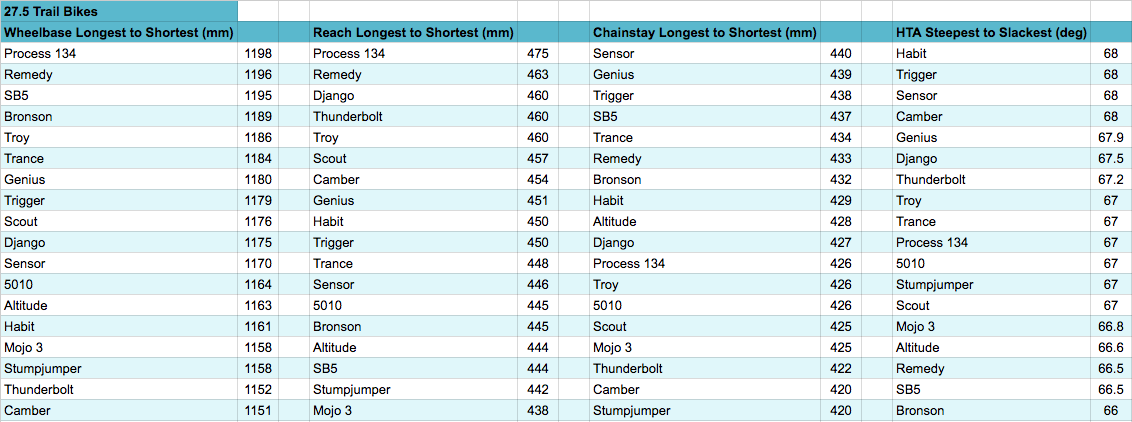

27.5″ Trail Bikes

Looking at this particular list of bikes, we can see that they tend to have more in common than not. While suspension travel varies from model to model, most of them have equal travel front and rear, or an extra 10mm up front. The exceptions are the Transition Scout, which has a 15mm differential front to rear, and the Yeti SB5, with a 23mm differential.

All else being held equal, adding additional travel to the front of the bike will slacken the head tube angle, raise the BB, and increase the wheelbase. Those things are great for descending, but too big a difference can lead to a bike with odd handling. For instance, if you had a bike with a 160mm fork and a 100mm shock, the front end would be able to handle much bigger hits than the rear. The result would be a bike that is unbalanced – a front end writing checks that the rear can’t cash.

As for the HTA, it seems that most manufacturers have found the sweet spot to be around 67 degrees, no matter how much travel the bike has. The slackest bike on this list is the Santa Cruz Bronson at 66 degrees, and the steepest is a four-way tie between the Habit, Trigger, Sensor, and Camber at 68 degrees. Considering the Bronson has more travel than most others on the list, the fact that it also has the slackest HTA is not surprising.

The ETT measurements average 622mm, and again, most bikes are within a handful of millimeters of that figure. Interestingly, the bike with the shortest top tube – at 605mm – is the Rocky Mountain Altitude which, like the Bronson, also happens to have more travel than the rest. It also has a shorter than average reach of 444mm. The shorter top tube and reach keep the Altitude’s wheelbase in check at 1163mm, which is 11mm shorter than average. In practical terms, this means the Altitude should still be nimble on tight trails even with all that travel. However, it has to sacrifice a bit in high-speed stability to achieve this.

As for the longest bike on this list, that award would go to the Kona Process 134. It has the longest top tube (645mm) and reach (475mm) figures, so naturally, it also winds up having the longest wheelbase at 1198mm.

Chainstay length for this bunch averages 429mm, with the GT Sensor having the longest stays at 440mm, and the shortest stays found on Specialized’s Camber and Stumpjumper. Specialized has always favored short chainstays, and in regards to the rest of the geometry, their bikes tend to have shorter top tubes, reaches, and wheelbases. This is a conscious decision on their part to retain the playful nature their bikes are known for.

Moving on to bottom bracket heights, we have an average of 338mm. Some companies don’t list BB heights and instead give BB drop, which is why there is data missing. Bottom bracket drop refers to the vertical distance between the center of the bottom bracket and the rear axle. It is important to note that these measurements are static – once you factor in suspension sag from the weight of the rider, the BB height will be lower. The lowest BB goes to the Camber (329mm) and the highest to the Cannondale Trigger (351mm). Like short chainstays, low BBs have long been a hallmark of Specialized’s mountain bikes.

Here are how the bikes stack up compared to one another in terms of wheelbase, reach, chainstay length, and head tube angle.

All right then, moving on to 29ers!

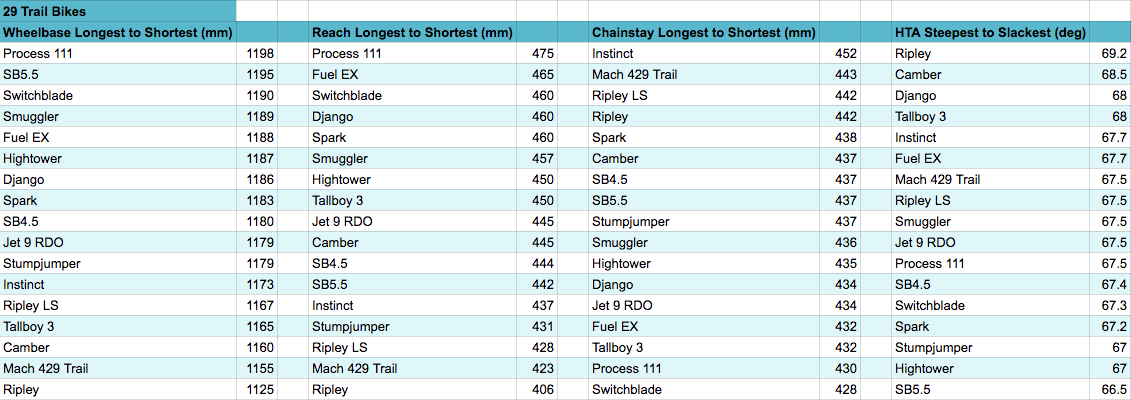

29″ Trail Bikes

29ers got a lot of hate when they first started popping up on the scene more than 15 years ago. Some of that was warranted, as many rode like microwaved dog shit, but a lot of the hate was simply pushback against something new. Sounds familiar, huh? We mountain bikers often forget that the mountain bike was not hatched from some magical egg where everything – the geometry, the components, its capabilities – came out fully-formed and perfect.

Would you ride a 1998 Trek Y-frame over a modern bike? If you said “yes,” you are what’s known as a “retro-grouch.” That said, 29ers have come a long way since their early awkward years, and the newest bikes can go toe-to-toe with any wheel size. Some riders still have their preference between wheel sizes, which is just fine. However, if you haven’t tried one, you are missing out.

Continuing the trend we observed with the 27.5″ bikes, the 29ers tend to have a suspension differential between 0 and 10mm, front to rear. Yeti once again has the biggest differentials on their bikes – 26mm on the SB4.5 and 20mm on the SB5.5. Average front travel for this group is 134mm and rear travel is 123mm. Most people would consider the bulk of this list to be firmly in the trail category. However, there are three bikes here that start to edge into enduro territory – the Pivot Switchblade, the Stumpjumper, and the Yeti SB5.5.

We also see that the average HTA is just one degree steeper than the average of the 27.5″ bikes. It seems you can’t go wrong with a 67-68 degree HTA no matter what bike you’re building. There is more variation in HTA on 29ers than 27.5″, though. Only two degrees separate the steepest from the slackest on the 27.5″ bikes, but there are 2.7 degrees of variation on the 29ers. As for the slackest bike, that would be the Yeti SB5.5 at 66.5 degrees with a 160mm-travel fork. The steepest bike is the Ibis Ripley at 69.2 degrees.

Speaking of the Ripley, Ibis offers the bike with two different geometry options. This isn’t achieved via a flip chip like some of the other bikes with adjustable geometry–instead, Ibis sells two completely different frames. The Ripley and Ripley LS (long and slack) have the same amount of travel, stack, and chainstay length, but everything else is different. The Ripley LS has a 1.7-degree slacker HTA, 22mm longer reach, a 6mm lower BB, and a wheelbase that measures 42mm longer. Taking all those seemingly small tweaks together creates two distinctly different bikes.

Average reach is 446mm, but as we saw with the HTA, there is a much broader range of measurements on the 29ers. The shortest bike in terms of reach is the Ripley at 406mm, and the longest is the Kona Process 111 at 475mm. That’s a whopping 69mm difference from shortest to longest. For the 27.5″ bikes, there was only a 37mm spread.

Getting to the back of the bikes, the chainstays on the 29ers are understandably longer than their 27.5″ counterparts. The Pivot Switchblade has impressively-short chainstays at 428mm, which was made possible by their repurposing of 12x157mm DH hub spacing. At the other end, we have the Rocky Mountain Instinct with 452mm stays.

With an average height of 335mm, bottom brackets are, on the whole, lower than the 27.5″ bikes. Why would this be the case? Good question. After some internal discussion, the best rationale we could come up with for this was to achieve a feeling of being “in” the bike instead of “on top” of the bike. I know from personal experience that my first 29er had a BB that was too high, leading to a tippy feeling in certain situations.

In terms of overall length, the 29ers have an average wheelbase of 1176mm, just 2mm longer than the 27.5″ average. Again, Kona takes the top spot for length with their Process 111 coming in at 1198mm. The shortest bike is the Ripley at 1125mm, which is actually shorter than all the 27.5″ bikes too.

Here are how the 29ers stack up compared to one another.

Conclusions

One more chart for you. This one compares the averages from the 27.5″ bikes to those of the 29ers.

This tells us that largely, there are minimal differences – at least in terms of geometry – between the average 27.5″ and 29″ trail bike. A 27.5″ trail bike will have a little more suspension travel, a slightly slacker HTA, a longer reach, shorter chainstays, a higher BB, and a shorter wheelbase. The biggest difference we see between the wheel sizes is in terms of the stack height. Remembering that this is the distance between the BB and the top of the head tube, it makes sense that the larger wheels would have higher stack heights. The larger the wheel, the higher the head tube will have to be. Stack height is often what prevents shorter riders from achieving a proper fit on a 29er – they can’t get their bars low enough. This can be remedied with a flat bar, which you often see spec’d on complete 29ers, or by using a negative rise stem. However, that solution works better on an XC bike than a trail bike where stems tend to be shorter in length.

The ideal head tube angle for trail bikes seems to be in the 67-68 degree range, and seat tube angles have settled around 74 degrees across the board. As covered above, we do see more variation between the 29ers than the 27.5″ bikes, which I found particularly interesting. For commercial purposes, the 29er has been around much longer than the 27.5. Because of this, I thought that 27.5 geometry would have been all over the map. My guess is that designers have used what they learned from both 26″ and 29″ geometry and applied it to 27.5.

While I wouldn’t go so far as to say there is an industry-wide consensus on trail bike geometry, we are seeing some crystallization on that front. A lot goes into designing and building a bicycle beyond the geometry – the suspension platform used, frame material, and component choice, just to name a few. Having ridden many of the bikes on these lists, it was interesting for me to see how similar some of them felt on the trail despite having different geometry – and vice versa. This is why it’s vital to consider a bike’s geometry in totality and not get hung up on just one or two stats like head tube angle and chainstay length.

And it’s also a reason to try before you buy!