I’ve got a lot of friends who love bikes, and I love them all, but there are few friends that I can talk as endlessly about bike tech as with Matt Dunn. To be fair, not everyone has the time or interest to stay up on the fast-paced evolution of mountain bike technology, and if it weren’t my job to sort through so much of it, I probably wouldn’t either. Some may call those people who aren’t obsessive, “people who have their priorities straight.” However, the same could be argued for both sides.

But some people, like Dunn, are obsessives — fanatics — who are always thinking about their optimal mountain bike and ways they could be better. A few readers may recognize his byline on some Singletracks reviews.

Last fall we were texting each other, about bikes, when he told me he was selling his full-suspension all-mountain bike. He was entering a serious hardtail phase. He’d sold a Ritchey HT in the past few years, and bought a more aggressively angled Stanton Sherpa with a 120mm fork and a custom build. Dunn is one of those riders that likes all kinds of bikes, from gravel to XC, to trail and enduro and he’s fast on all of them.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised when he told me he’d forego another full-suspension bike for an enduro hardtail with geometry he selected himself.

“I started in mountain biking by having the bike that was the wrong size completely for several bikes,” he said. “And most mountain bikers will buy the wrong size for certain reasons. Sometimes it’s the salesman at the bike store. Sometimes it’s because you come from BMX and a mountain bike is too big. There’s all these reasons people buy mountain bikes that don’t fit.”

People put a lot of trust into engineers at bike brands when they are on the hunt for a new bike. Brands continuously analyze their competition and evolve geometry with suspension and other design considerations, but to Dunn’s point, they are designing geometry for a very wide spectrum of riders, assuming that the numbers will work for the most people in a given height range. Classic bell curve scenario. After buying bikes according to size, like most would shop for a t-shirt, Dunn wanted to try something different.

“I was too curious,” he said. “I needed to know what it was like, because I looked at all these bikes, and yeah, they’re awesome, but I want to know what it’s like to have a custom-tailored suit. I want to know what it’s like to ride the bike that I designed.”

While it may sound like he bought a whiteboard and dry-erase markers and started experimenting, his process wasn’t quite as rigorous, although he had plenty of background information from riding different bikes he liked and didn’t like over the years. Instead, he started with a spreadsheet with 20 bikes he was interested in, averaged the geometry, and reviewed the numbers. He included bikes he owned and was familiar with, from another hardtail, his former full-suspension, and a fat bike, splitting hairs and analyzing the differences.

He’d get through one average geometry draft and eliminate a few models because of numbers that were sticking points. Maybe the reach was too long or the seat tube angle too slack. Whatever the case was, it was off his list, and the list got smaller and smaller until he had five bikes and the average geometry of them. Then he sent the idea to Axial Bikes, a custom frame builder based in Colorado—after a few beers and more contemplation.

Even though he had a strong concept of the numbers he wanted and it was validated through a competitive analysis of his own, it was a heavy decision. Bikes are expensive, he wouldn’t be able to test it beforehand, and “once I pull the trigger on custom geometry, it’s permanent,” he said.

Then, came a long thread of emails between him and GP at Axial.

The right lines

There were two numbers that held the utmost importance to Dunn and similarly to a lot of people: the reach and effective top tube length. He wanted enough reach for stability and enough cockpit room so he wouldn’t be slamming his knees into the stem—but not so long that he couldn’t get a hold on the pony.

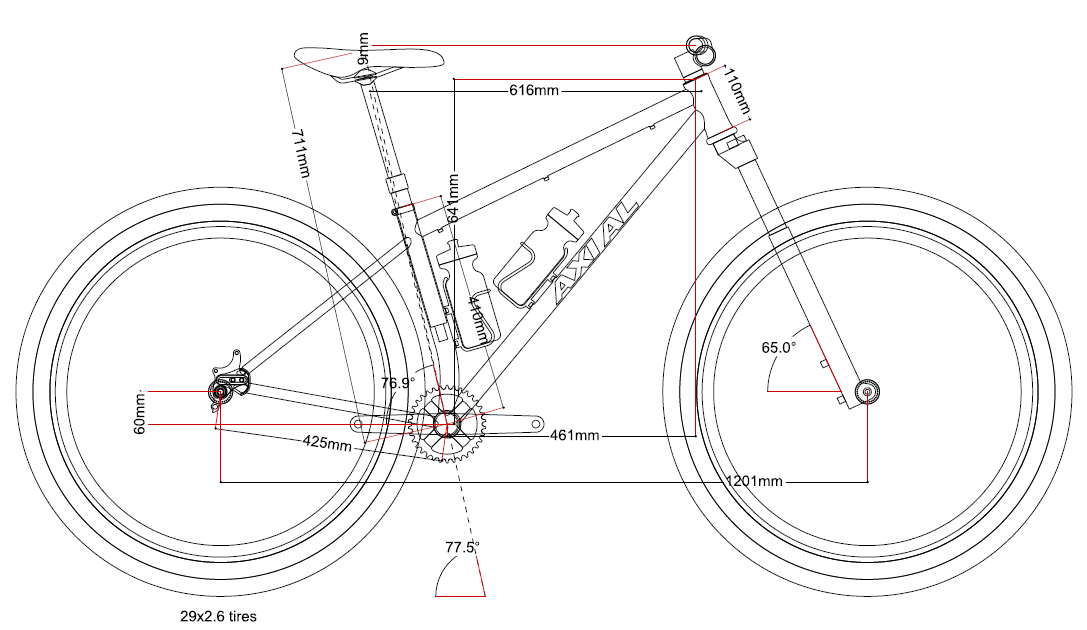

But less important doesn’t mean not important. At 1,201mm, the wheelbase is lengthy for a size “medium” hardtail.

The chain stay length could have been another nail biter, but Dunn paid $100 for sliding dropouts, giving him adjustable chain stay length, from 425mm to 440mm, which would also change the wheelbase length.

“I said, I’ll do sliding dropouts so I can go shorter or longer and I won’t have to decide that,” he laughed.

Lastly, he weighed the differences between a 110mm or 120mm head tube length. 120mm meant that he likely wouldn’t need to run any stem spacers, for a cleaner aesthetic. It also meant that he couldn’t run any stem spacers if he wanted to switch up the stack height. Axial nudged him toward a shorter head tube, just in case.

All in all, they sent 90 emails between the first and final, sixth draft. Between the fifth and sixth, they made the head tube length decision and decided that all the final measurements should be at sag, assuming the fork rested about a half-degree forward, 20% into its travel.

Love at first ride?

There are first rides and then there are first tests. The first thing he did after he picked up the bike from GP was the parking lot bunny hop. Even at the 425mm chain stay length, it wasn’t quite as poppy as he imagined it would be.

Winter being what it is in Colorado, Dunn didn’t have many trails available to test his new rig when it was ready. He found a short, dry trail with some steep and loose sections he could get a feel for it on. Though he’d been along every step of the way as his frame was designed and built, he wasn’t sure what to make of it yet.

“The first descent, I felt like it was a little bigger than I expected, a little more unwieldy,” he said. “But then I reminded myself, ‘Oh yeah, I built an enduro hardtail,’” and he plans on racing it.

The other surprise was how compliant the bike felt—more-so than any other steel hardtail he’d owned. Being a custom bike, the designer didn’t have to produce it for a weight range within a height range to meet safety standards. The Axial was built to Dunn’s height and weight. “It just flutters,” along choppy trail, he said. “When you get a custom bike, you get that real steel feel that everybody knows about steel. There’s a whole other layer.”

Til infinity…

Expectations aside, the frame fit like a glove for its intent. He has a shorter-travel hardtail for longer rides on mellower trails and this one will see some racing this summer.

Will it suffice and stave off other full-suspensions? Dunn is optimistic. His friends are less so, trying to convince him he’ll have a full-suspension again after a year. Though the geometry is aggressive and he’s a great rider, there’s still no substitution for rear travel on big hits.

Either way, this custom bike isn’t going anywhere soon.

“I feel like we’re at a good pause point in technology in the industry,” he said. “We already got through Boost, we already got through the angle changes and the design changes. We got through a lot of stuff. I felt like we were in a good spot to make it a permanent, settled bike.”

But if technological change does eventually outpace his frame and maintenance gets to be too much, he’ll strip it and hang it like steel-tubed art—a frame that will never be filled. Selling it to another rider, he says, would require finding someone with very close dimensions, limiting the potential pool of buyers.

“It’s a keep-forever bike. If not, then it’ll be a frame I put on my wall.”