It’s a question land managers and owners, trail workers, and trail groups often face: Will they be liable for mountain bikers’ potential injuries?

This article summarizes the laws in British Columbia (BC), Canada concerning liability arising from trail work on recreational trails, so it doesn’t apply broadly. However, this analysis should be helpful for anyone who has considered this topic. Also, this article doesn’t concern itself with liability of commercial operations (bike parks or any areas where an access fee is charged). For more about liability for commercial operations on trails, look for a follow-up article soon.

The audience for this article is land owners, land managers, and trail organizations. It also has relevance to sanctioned trail workers since many land owners/managers will try to offload liability or blame onto trail groups or trail workers. The gist of this article is that provincial BC law has made it practically impossible for non-commercial trail organizations or independent builders to get sued for the work they do on the trails, and explains why this is the case.

Disclaimer

As opposed to legalese, the article will strive to use plain-language (sometimes known as English) as much as possible. Now for the disclaimer: I am a lawyer whose main area of practice is in technology, specializing in commercializing intellectual property. I also do a fair amount of trail work and volunteer time in trail advocacy, hence my interest in the intersection between the law and mountain biking.

Having said that, I have no personal expertise in personal injury law (other than a keen interest) so my comments on the Occupiers Liability Act (OLA) and all related decisions are very general in nature. Furthermore, although I am a lawyer I am NOT your lawyer. Do not take any of this article or any comments I may make as legal advice.

Occupiers Liability and the law in BC

In British Columbia legal exposure for landowners and land managers is outlined in the Occupiers Liability Act (OLA). The OLA was amended in 1998 primarily to give comfort that routing the TransCanada trail through private property wouldn’t expose land owners to lawsuits from trail users. The OLA amendments established a standard so that land owners and managers have exceptionally limited exposure to liability from trail users.

The success of the OLA can be seen in the paucity of BC case law testing it. Since the amendments have been passed, trail users rarely sue land owners or managers, and when they do, the trail user loses. One could speculate that a reason is that trail users and the litigation bar have become more sensible. However, a more reasonable inference (and one that the author believes to be true) is that the OLA is so overwhelmingly protective of land owners/managers that trail users look elsewhere for blame when they get injured on recreational trails.

Relaxed vs standard duty of care

Trail organizations and independent builders work on trails primarily on public lands. The OLA addresses “Occupiers” and their “Premises” and spells out the liability faced by Occupiers from a user of such Premises.

Under the OLA, an “Occupier” is a private land owner or a public land manager (ie a municipality, province of BC, Regional District, or licensee of occupation of some land). In addition, a trail organization or independent builder sanctioned to do trail work is also considered to be an Occupier1. The Occupier’s “Premises” is land or structures2. There are two levels of responsibility that a land manager or landowner has to a user of a land. The first is a diminished or ”relaxed” duty of care and the second is the “standard” duty of care.

The “relaxed” duty of care applies to all trail users not paying a fee to access certain categories of land. Such trail users are deemed to have “willingly assumed” all risks with using these specific land categories. The land owner or manager would only be liable to the trail users if they: (i) did something to intentionally injure the trail user; or (ii) acted with “reckless disregard”. 3 Only certain categories of land are covered under the “relaxed” duty of care. However, the broad, sweeping OLA language extends to all trails or rural lands.4

The “standard,” more onerous duty of care, is the duty of care familiar to personal injury lawyers throughout the world. This applies to owners charging an access fee, to non-”Occupiers” (for example, independent, unsanctioned builders), and to managers of non-recreational, non-rural land (for example, urban skills parks, skate parks, etc.). In these instances, it is deemed that a user has not willingly assumed risks. Here, standard negligence principles apply and the test would be if the land owner or manager in question takes standard “reasonable precautions.” Note that a trail organization charging a trail membership fee or selling some sort of trail pass for using trails is not considered to be a commercial operation, so the group is still under the “relaxed” and not “standard” duty of care.

These “standard” duty of care principles are outside the scope of this article. If you need further information about that contact your lawyer (remember that’s not me).5

Relaxed duty of care

Mountain-bikers riding in non-commercial areas are owed a diminished or ”relaxed” duty of care when on land for the “purpose of a recreational activity” and on “recreational trails” located on ”rural premises.” (The BC courts have given that category of land a very wide reading as summarized in this David Hay article.) If you got hurt while mountain biking on recreational trails, the OLA wording means that any lawsuit you launch will have a small chance of getting off the ground.

In the interest of being thorough, let’s look at this small chance from the vantage point of a land manager or owner. You own some land and someone is using the land perhaps by building a trail on the land or recreating on it. The government has a deliberate policy of promoting land access, thus lessening your exposure as a land manager/owner to lawsuits from trail users. The OLA doesn’t mean you have zero duty of care to mountain bikers on your land. It just means that you have a very low duty of care.

How low? You don’t even have to take “reasonable care” to not injure someone (that is the codeword for the stricter “standard” duty of care). If you act with “reckless disregard” you are liable to the trail user. If you intentionally try to harm or damage the trail user, you are liable to the trail user. These are pretty low bars to meet. You as a land owner or manager don’t have to try very hard to fall under OLA protection.

“Reckless disregard”

It’s reasonable to assume any sane land manager or owner (or trailbuilder for that matter) isn’t going to try to intentionally injure a trail user, so I’ll leave speculation on that scenario to others. Let’s instead look at “reckless disregard” (under the OLA “relaxed duty of care,” the only way for a land owner or manager to be liable to mountain bikers on recreational trails) and what that actually means.

Normally one would turn to legal cases where the OLA had been tested in court (sometimes also called precedent) to get some insight into what “reckless disregard” might mean for mountain bike trails. However, for mountain bike trails in BC, these types of cases have not gone to trial resulting in precedent. And as previously opined, it is the author’s opinion that the reason there aren’t a lot of cases is because the OLA establishes so much protection for BC landowners and land managers that plaintiffs don’t even try.

Lawyer Mary MacGregor has a useful interpretation of “reckless disregard” (written in 1998) that’s worthwhile reproducing in its entirety

In order to be acting with reckless disregard, you must first be aware of the presence of people on your property, or you must be aware that their presence in the future is very probable. As well, you must do something, or fail to do something, that is likely to cause damage or injury, without caring whether that damage or injury results.

As an illustration, let’s suppose that you have a private road, which is marked as such. You know that, despite your “no trespassing signs” people sneak down the road at night from time to time even though they are not supposed to. Then you decide to dig a deep trench across the road and you remove the material from the trench so that the trench is hard to see. You do not lock or block off the roadway nor do you take steps to warn of the danger. If someone then drives into the trench at night, injuring themselves and their vehicle, a judge is likely to think that you acted in “reckless disregard” for the safety of people that you knew might possibly make use of the area.

But even Ms. MacGregor’s example might have too generous an interpretation of “reckless disregard.”

In 2008, the BC Court of Appeal created precedent in Skopnik vs BC Rail. In this case Skopnick rode an ATV along a BC Rail right of way (ROW). He hit an old ditch and was injured. In considering “reckless disregard” the court said that the test ” …means doing or omitting to do something which he or she should recognize as likely to cause damage or injury to [the trail user] present on his or her premises, not caring whether such damage or injury results“. BC Rail admitted that it …” . did not maintain the ROW with a view to the safety of trespassers or recreationists on the ROW“. BC Rail didn’t inspect the rail right of way and only inspected tracks. They had no maintenance or reporting program for the railbed and responded only if someone complained. This wasn’t enough to invite a “reckless disregard” finding so the court found BC Rail to not be liable.

This leads to the curious conclusion where a land owner or manager which doesn’t have an inspection or maintenance program is better off than one who does. Also inferred from the BC decision is a land manager could simply ignore knowledge of people recreating on their trails and abdicate responsibility to maintain the trail (unless there was a complaint). The hands-off approach was not “reckless disregard” and did not invite liability.

What about the rest of Canada?

A useful article by lawyer Dianne Saxe written in 2012 compares the Occupier Liabiliy Statutes of many of the rest of Canadian provinces concluding that British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia have all enacted versions of OLA’s specifically saying that users of recreational trails are owed a diminished/”relaxed” duty of care. In other words, in these provinces land owners and managers don’t even have to take “reasonable care” to not injure someone. All they have to do is not do something to deliberately injure trail users or act with “reckless disregard”.

Only in Ontario have there been cases considering occupiers’ liability and reckless disregard. Showing the diversity (and confusion) of law, Ontario courts have come to different conclusions than the BC courts holding that some Ontario cities were liable and showed “reckless disregard,” primarily in situations where the cities have had inspection and maintenance regimes on recreational trails and not followed those regimes.

The Ontario Superior Court considered “reckless disregard” in the 2014 case of Herbert (Litigation Guardian of) v. Brantford (City). In this case the plaintiff cyclist became a quadraplegic when he went off trail. The Ontario Court applied the same “reckless disregard” definition as the BC Court did in 2008 — “doing or omitting to do something which he or she should recognize as likely to cause damage or injury to [the trail user] present on his or her premises, not caring whether such damage or injury results.“

However, the court came to a different conclusion finding the city partially liable on the grounds that they had a regular trail inspection routine, knew that the particular section of trail was narrow, and knew that the particular section of trail could involve collisions between users.

In the 2014 case of Cotnam vs National Capital Commission the plaintiff’s case was shot down almost immediately by another Ontario court. In this case the plaintiff was injured riding a recreational path in Ottawa and alleged inadequate warning signage. The inadequate signage was held to not be “reckless disregard.” In the 2009 case of Kennedy vs City of London, the City was held to be in “reckless disregard” for placing a bollard in the middle of a recreational trail without marking it. The plaintiff cyclist hit the bollard and was injured.

Meanwhile in the 2004 Dally vs City of London a plaintiff rollerblader injured herself on a recreational trail. The city was held to be partially liable for the injuries because it advertised a hazard reporting system, instituted a maintenance and reporting program, and then didn’t carry through with it consistently.

The message is that in Ontario a land owner or manager who has an inspection or maintenance regime had better follow that regime and apply it consistently. Failure to do so defeats the extensive protection of the OLA and exposes the land owner or manager to potential liability. Does this mean that a land owner/manager is better off following the BC Rail example? This has never been litigated and since nobody wants to volunteer to be a test case, there may never be definitive answer to that question.

For trail associations and independent builders

So why the lawyer bafflegab and overkill?

As mountain biking has matured, more and more trail work is becoming sanctioned. The Province in BC is now promoting mountain biking after recognizing it as a key economic driver.

Primarily it is BC land managers driving this process in an effort to get a handle on the disparate, massive trail systems built by a motivated, creative network of independently-minded, highly-opinionated (and volunteer) trail artists. Many of these trail workers have now banded together into associations to formalize trail work while others still work independently.

Almost all trail associations are now faced with the juxtaposition of formalized government bureaucratic processes being married to somewhat anarchic and ad-hoc trail building and maintenance efforts by thousands of volunteers. One tension in this uneasy marriage is the imposition of legal mechanisms to allocate risk among land managers and trail workers.

Insurance and trail organizations

This article has already explained why land managers have next to no legal exposure to trail users. Yet volunteer trail builders and volunteer trail organizations frequently have government bureaucrats impose legal obligations on them. Is this fair? Should a government that is seeking to derive benefit from trail systems built and maintained by volunteers then seek to transfer risk to those same volunteers?

Well, the government certainly does not shy away from doing so by way of indemnity clauses. The usual wording is something like, “TrailBros of Pleasantville indemnify the town of Podunk and the Province of BC for everything under the sun.”

Land managers rely on this legal gobbledygook to shift risk to volunteers for the volunteer work done on trails. This is risk that barely exists due to the OLA, a provincial law created for the benefit of the province. Not only does the Province of BC have the ability to manage its own risk through passing laws, it has its own insurance schemes. This begs the question: is it a fair policy for the provincial government to then lay the risk onto volunteers? And what risk!

Leaving aside that this legal bafflegab is unfair and onerous, it is also potentially toothless. A volunteer trail organization is only liable to the extent it has assets. If the trail group has no insurance and someone sues it, the trail org becomes insolvent, hands over its tool kitty and beer fund, and leaves the land manager holding the bag of legal defense.

But wait! What bag? Remember that the land manager/province wrote a law that made it well nigh-impossible to find liability against the land manager unless it went out of its way to “intentionally injure” a trail user or the land manager acted with “reckless disregard.”

If the trail group has insurance then the insurance is an asset but the organization had to pay thousands of dollars a year for. Those dollars could have been better spent on trail work if the land manager/province instead insured the volunteer trail group working on public trails on public lands. This comment argues that the Province is in the best position to assume that risk. To repeat, the Province has the ability to constrain the risk (it wrote the law remember?) and derives benefit from the volunteer trail organizations.

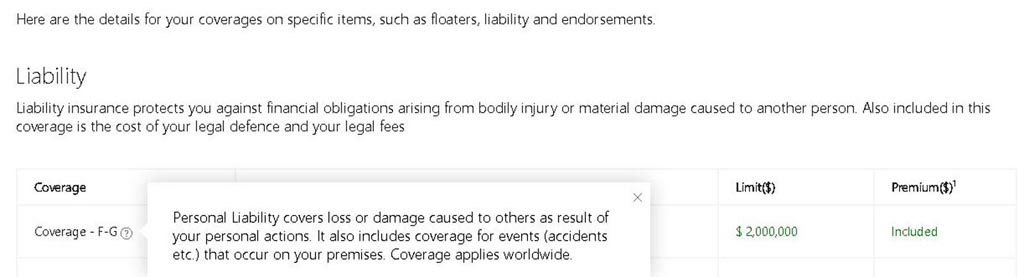

That all being said, a tip of the hat is then due to RSTBC which offers $2 million in comprehensive general liability insurance to trail organizations and others who sign up for a Partnership Agreement with RSTBC permitting them to work on and maintain trails. Certainly this is fair and a positive inducement for people to work with RSTBC.

So what does a trail organization who’s jumped through hoops and is now a lawful “occupier” of land buy when they get insurance? We’ve already seen that short of the trail organization doing something malicious to literally try to hurt a trail user, the trail organization cannot be held liable. They are protected by the OLA. What insurance buys is legal fees. It’s a free country and anyone can sue; insurance pays for your legal defense. This begs the question whether insurance should be this expensive, but that topic is a question for actuarial calculations.

Independent builders

If you are an unsanctioned builder (a nice tip of the hat to unsanctioned builders by Bryce Borlick for the Revelstoke Mountaineer) you are not an “Occupier” per the OLA. There have been no test cases where unsanctioned builders have been sued. My opinion is that there is a lack of test cases because you don’t sue empty pockets. Instead plaintiffs go after land managers (hence the OLA)

The exception to the above generalization is if the independent builder has homeowners or renter’s insurance. Such insurance will cover that builder’s legal expenses or any damages they cause in the course of doing their trail work or maintenance. A land manager, land owner, or other “Occupier” of land would still be practically immune from liability by virtue of OLA protection.

From the perspective of the independent, unsanctioned trail builder, if there were test cases for biking, almost all analogous situations would be looked at from the perspective of skiing. In skiing situations the standard non-OLA duty of care in sports with inherent risk means that you would have to have some sort of monumental, colossal series of almost intentional mistakes to be held liable. For their own reasons, BC courts have consistently adopted an anti-plaintiff stance in “inherent risk” sports. It is a reasonable inference that cases against unsanctioned independent builders would go the same way (ie badly for a plaintiff).

End notes

- “Occupier” is “a person who (a) is in physical possession of premises, or (b) has responsibility for, and control over, the condition of premises, the activities conducted on those premises and the persons allowed to enter those premises, and, for [the OLA], there may be more than one occupier of the same premises”.

- “Premises includes: (a) land and structures or either of them, excepting portable structures and equipment other than those described in paragraph (c), (b) ships and vessels, (c) trailers and portable structures designed or used for a residence, business or shelter, and (d) railway locomotives, railway cars, vehicles and aircraft while not in operation”.

- Section 3(3) of the OLA, states that “[d]espite subsection (1), an occupier has no duty of care to a person in respect to risks willingly assumed by that person other than a duty not to (a) create a danger with intent to do harm to the person or damage to the person’s property, or (b) act with reckless disregard to the safety of the person or the integrity of the person’s property.”

- Section 3.3 of the OLA refers to these categories of land – “Rural Premises”, “Recreational trails reasonably marked as recreational trails”, “private roads marked as private roads”, “forested or wilderness premises”, “vacant or undeveloped premises”. See the case of Hindley vs Waterfront Properties where the BC Supreme Court gave a broad reading of the meaning of “rural premises” holding that an undeveloped parcel of land even though within Parksville municipal boundaries was “rural premises” and therefore that any trail users of that land were only owed a “relaxed” duty of care.

- Section 3(1) of the OLA, states that “an occupier of premises owes a duty to take that care that in all the circumstances of the case is reasonable to see that a person, and the person’s property, on the premises, and property on the premises of a person, whether or not that person personally enters on the premises, will be reasonably safe in using the premises”.

Resources and references:

- David Hay article (2007) “The Wild Game of Occupiers Liability” re Occupiers Liability in BC

- Mary MacGregor article (2008) “Occupiers Liability Act Amended” re Occupiers Liability in BC.

- Dianne Saxe article (2012) “Liability for Recreational Trails.re Occupiers Liability generally in Canada

- Graham Litman and Matt Hulse article ”ENHANCING PUBLIC ACCESS TO PRIVATELY OWNED WILD LANDS” re Trespass, Occupiers Liability and Right to Roam laws