Take a look at an average kids bike, say from a big box department store. There is of course nothing that disqualifies it as a bike: it has two wheels (four counting training wheels), a set of handlebars, a saddle, cranks, pedals, and a chain. Then, take note of the geometry or the angles of the frame tubes and where the contact points lie. The saddle is low — sure, kids at this age need to reach the ground with their feet, but the handlebars are often several inches above the saddle. Though most kids can reach the handlebars just fine, this position places the majority of the kid’s weight over the rear wheel, potentially unweighting the front wheel to the rider’s detriment, and the seating position often limits full extension of the legs, making it harder to pedal.

What does all this mumbo jumbo mean for kids trying pedal some of their first bikes around the neighborhood? Depending on the bike, the kid may be in a suboptimal pedaling position and could have a tough time getting into motion, keeping their speed, or even steering the bike. Many of us adult cyclists can’t imagine pedaling a bike in this position without phantom knee pain.

Todd Carver had a hunch after seeing his kids ride their bikes. The stack height; how high the handlebars sit relative to the rider, looked too high. The reach, or how far away the handlebars are from the rider looked too long, and the seat tube angle, which puts the rider farther back over the rear wheel, looked too slack.

“If you asked me to hop on a bike and ride with those same angles, I probably wouldn’t ride it,” says Carver, head of human performance at Specialized and an original developer of Retül, a 3D, motion capture bike fit system. Like any inquisitive fitter, Carver had to find out what was going on, so he hooked his kids up to the Retül motion capture fit equipment he had set up in his garage and analyzed their positions and the geometry.

The fit confirmed what Carver thought he saw, at least on the Specialized Riprocks the kids were riding. About 80% of the rider weight was over the rear wheel with only 20% over the front. The crank length was too long and the stance width or Q-factor was too wide. As suspected, the stack height was too high, and the reach too long.

“The problem I saw, especially in my own kids was that they had to work so hard to pedal a certain speed, to keep up, and they also had a lot of problems controlling the front wheel,” says Carver.

Carver co-founded Retül in 2007 with Cliff Simms and Frank Vatterott to make bike fitting as precise as possible. Retül uses 3D motion capture technology, measuring everything from rider weight distribution, to lateral knee movement throughout the pedal stroke, hip angle, and the height of the rider’s arch in their feet to make a proper shoe recommendation.

Retül made an offer to us that if we could wrangle up a kid and take them up to their headquarters at the Specialized Experience Center in Boulder, then we could see how the fit process works for kids and why it’s advantageous. Ahead of the visit, I thought the idea may be unnecessary. I saw the value in a bike fit after my first road bike purchase years ago when my knees began to creak after long rides. But, most kids aren’t riding their bikes for 50+ miles, and they quickly grow out of bikes. Fortunately, I was getting ahead of myself.

My wife Hannah and I picked up our 6-year-old nephew Jackson after school one day in April and drove up to Boulder. Jackson wasn’t entirely sure what he was getting into, but he knew it involved bikes and had been telling his friends and family about it the week leading up to the bike fit. Jackson is a new rider and is just learning the basics. Over the winter, Hannah and I had spent a few hours with Jackson and his brother riding — or rather, scooting down the bike path. The weekend before the fitting, Jackson logged some more ride time with his parents and made some serious progress.

Jackson’s bike is a typical kid’s bike, like most of us learn on. But, thinking back to the time we rode with him, we saw many of the challenges Carver mentioned. A handlebar height that seemed too high and weight distribution primarily over the rear wheel.

As we walked into the polished Specialized Experience Center showroom, Jackson gazed at the fancy rigs decorating the interior. He hoisted a 15lb road bike off the ground, checked out a bright yellow e-bike, and finally the minty Specialized Riprock 20 he’d be acquainted with for the evening.

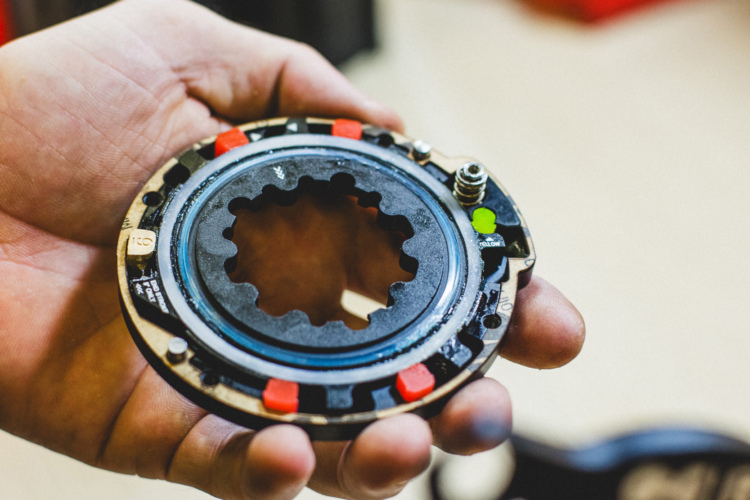

Carver set up the Riprock on the Retül platform, measured the bike with the magic wand-like Zin tool, and put little dots along Jackson’s shoulders, back, knees, and ankles. The dots then connect to a string of motion capture instruments to get Jackson’s exact movements on board the Riprock.

Carver entered Jackson’s information into the Retül system. Retül uses rider data en masse to inform fit and geometry on all Specialized bikes, from sleek time trial bikes to kids bikes like the Riprock.

As far as weight distribution on a kids bike, it doesn’t need to be equal front and rear, like an adult cross-country bike, “Because they’re kids and we don’t want to have it be too unsafe and too performance [heavy],” says Carver. “We want them to have a sense of security and safety, but too far back is also bad because then you have no weight on your front wheel.”

A weight distribution that’s around 60/40 on the rear and front is a good goal, and that’s what Specialized sought with their latest Riprocks after rethinking the geometry. Most parents probably won’t care too much to get their kids a custom bike fit, but if the concept is already built into the bike, then it may seem more sensible. The team at Specialized showed us their Jett 20 with measurements on the handlebars so they can be rotated in or out as the kid grows and extra holes in the crank arms so the pedals can be in a shorter or longer position.

After analyzing Jackson’s movements in one position for a few minutes, Carver brought the saddle height up with the Riprock in the Retül stand, and with the seat higher, Jackson accelerated the wheel more quickly and more easily. With better range of motion, Jackson’s knees moved in a straighter line, according to the Retül motion capture instruments. Did it feel easier? “Yeah,” said Jackson.

Before long, Jackson was ready to hop off the stationary bike and take it out on the trails. The riding position was different than his bike at home, as were the disc brakes — a grabby departure from the coaster brakes he’s used to.

Don’t take this experience as gospel. Jackson is just one kid and this experience for us was anecdotal, but he excelled on the Riprock considering he has only ridden a bike without training wheels a handful of times. It was apparent that the geometry of the bike played some role, big or small.

We pedaled down to Valmont Bike Park on a bike path and then section of natural surface trail and he seemed to have a more natural sense of handling. On small hills, he’d pick up a fret-worthy amount of speed, and steer through trees, around corners and objects, slowing himself in the grass if he needed or as a last resort, with the brakes.

And, I’m not sure if it was the shiny new bike, pedaling in the foreground of the Flatirons, or having a small media team chasing him around, but Jackson seemed to enjoy himself much more than the previous time Hannah and I rode with him. Spill after spill, he picked the bike back up and kept exploring Valmont.

I can see where a lot of people may deem a geometry revolution in kids bikes as unnecessary. Kids outgrow bikes as fast as they do clothes, and bikes like the Jett or Riprock, priced at $550 and $650, are an expensive choice for some, especially compared to the $80 Huffy pictured above. Jackson wasn’t prepared for an interview about riding the Riprock, but he did say it felt easier to ride than his other bike. He also like “the brakes” and “the color.” He’s probably not concerned with geometry and weight distribution yet, but if they’re separate ingredients in a recipe that make a bike more fun, on top of the color and the brakes, then he likely won’t notice the vegetables along with the desert.

5 Comments

May 20, 2022

Dec 18, 2022

May 22, 2022

May 19, 2022

Oh yeah..... dessert

Jan 26, 2023