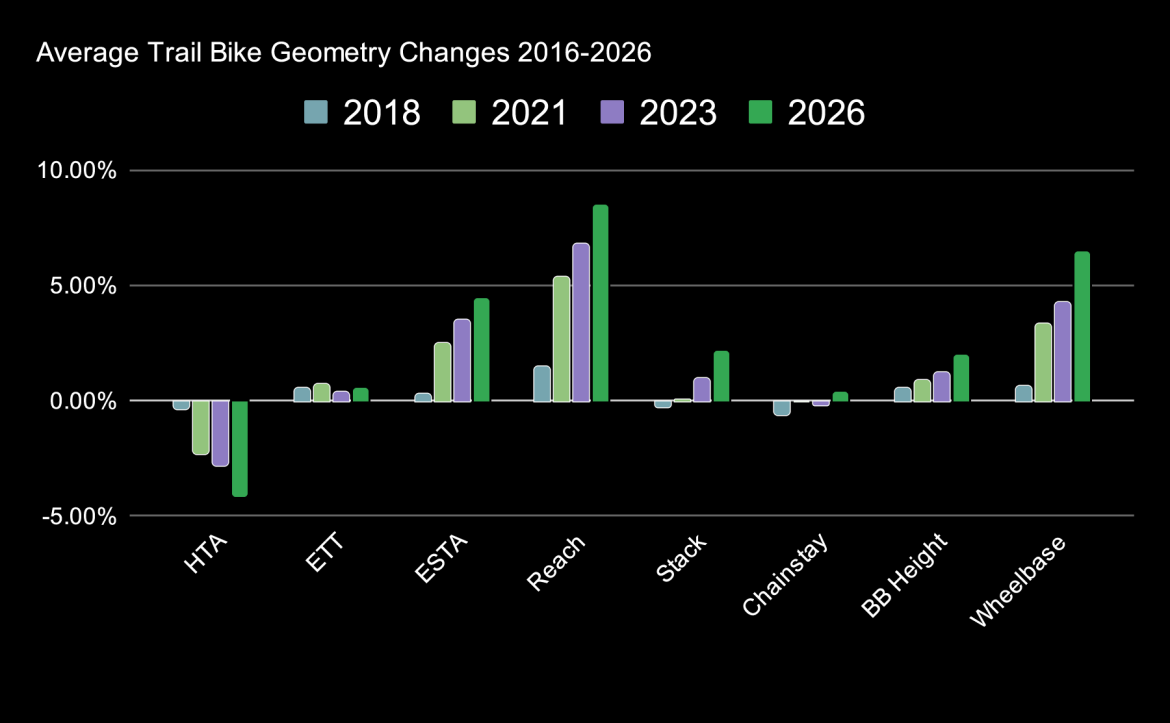

Singletracks has been tracking and analyzing trail bike geometry since 2016, and to state the obvious, there have been big changes over the past 10 years. There’s been some speculation that geometry changes are slowing, though looking at the data, that doesn’t appear to be the case. However, we are seeing glimpses of convergence when it comes to key numbers like head tube angles.

Reaches are getting longer still, though mountain bikers may have reached their limit

In 2024, we asked Singletracks readers if mountain bike reaches were too long, and 45% of you said yes, while just 5% said they wanted even longer reaches. Though some recently updated bikes saw shorter reaches—most notably the Commencal Meta SX V5, which saw its reach drop from 495mm to 480mm—the average trail bike reach increased by 7.5mm between late 2023 and early 2026, a significant jump in a short period of time.

Because it can be several years between mountain bike model updates, geometry changes tend to lag rider preferences. As such, we predict that it will be a couple of years before we see reach numbers plateau and perhaps eventually begin to fall.

Modern head tube angles are slacker for good reason

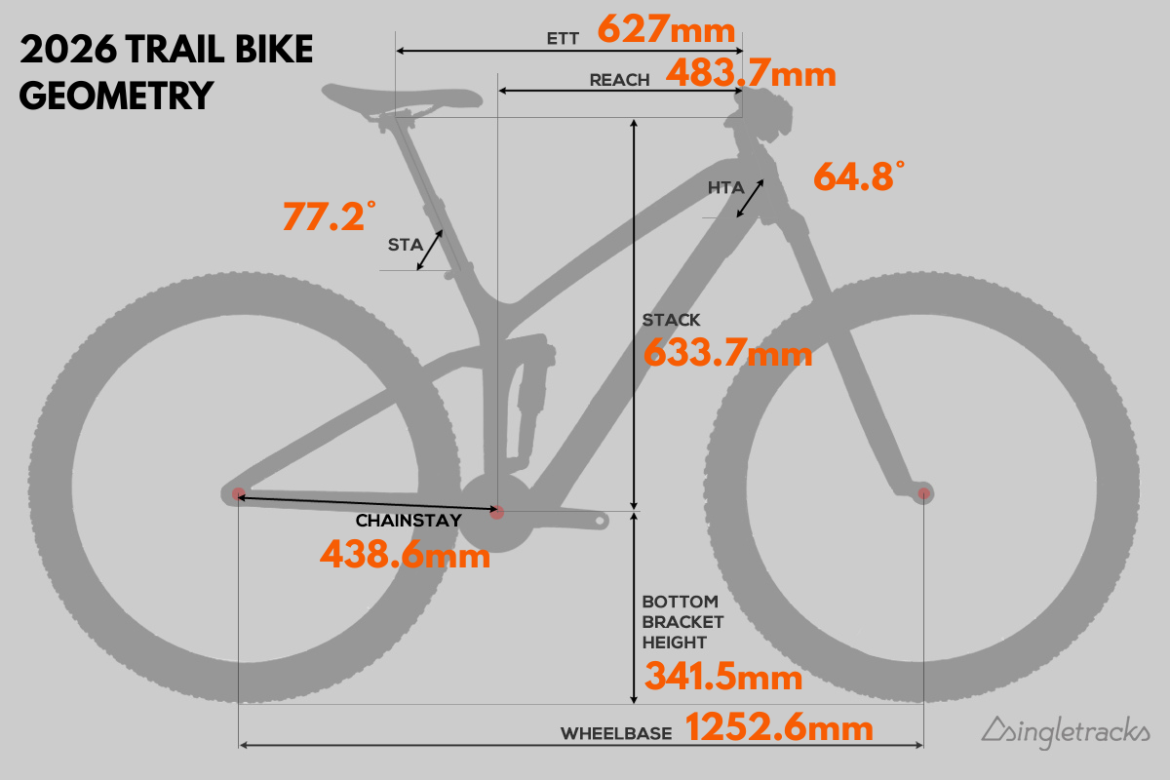

Perhaps even more significant than longer reaches, the average trail bike head tube angle dropped almost a full degree in just two seasons. Back in 2016, when we first started tracking trail bike geometry, head tube angles averaged 68°; today, the number sits at 64.8°.

Now, the cynic might assume that these changes are being driven by the bike industry chasing the latest trends, but it turns out there’s also a simple explanation. Looking at today’s trail bike geometry numbers, there’s a very strong correlation between a bike’s front suspension travel and its head tube angle.

| Fork travel | Head tube angle |

|---|---|

| 140mm | 65.3° |

| 150mm | 64.7° |

| 160mm | 64.3° |

While head tube angles were getting slacker, trail bikes were gaining travel, too. In 2016, the most popular trail bikes averaged 138mm/129mm of suspension travel front/rear, which is roughly a 140mm/130mm bike. Today, the average trail bike has 10mm more suspension travel front and rear, 150/139mm. For example, look at one of the best-selling trail bikes, the Specialized Stumpjumper. Two years ago, the Stumpy was a 140/130mm bike; now it’s specced with 160/145mm of travel front/rear.

Trail bike head tube angles have become slacker, in part, simply because modern trail bikes have longer forks.

At the same time, we’re seeing head tube angles converge significantly, which suggests that there is an angle that’s right for a given amount of travel. Just two seasons ago, the popular trail bikes we looked at had head tube angles ranging between 63.8° and 67.5°, a difference of 3.7°. Today, that range is 64-66°, a difference of just two degrees.

| Rear suspension travel | Bottom bracket height |

|---|---|

| 130mm | 337.8mm |

| 140mm | 340mm |

| 150mm | 347mm |

Bottom bracket height (the “lower” part of longer, lower, slacker) is typically measured from a static position, which means it’s heavily correlated with rear suspension travel. With more travel, and given the same percentage sag, a trail bike needs to start from a higher bottom bracket height to reach roughly the same sagged height.

Over the past several seasons, we’ve seen riders moving to shorter cranks, which in theory allows bottom bracket heights to move lower rather than higher, though so far there’s no indication that’s happening. It’s possible that, without shorter cranks, bottom bracket heights would have increased even more.

To put the idea of lower trail bikes in context, wheel size is an important consideration. Early 29ers were mostly XC-style bikes, and as the big wheels moved into trail bike territory, they brought with them larger bottom bracket drops. In our 2016 and 2018 analyses, we looked at 27.5″ and 29″ bikes separately and found that on average, 29ers had slightly lower bottom bracket heights. As the wheel size gained popularity, it certainly influenced bottom bracket heights lower, though not by much, and not enough to offset what was happening with rear suspension travel numbers.

Bottom line: longer, lower, and slacker has been driven, in part, by trail bikes gaining suspension travel over time.

Is geometry or travel better for categorizing mountain bikes?

This question comes up among mountain bikers regularly, including in the comments section of our Trail Bike of the Year coverage and this recent Reddit thread. On some level, we want to believe that geometry is the secret sauce that makes one brand’s trail bike ride differently from another. To some degree, that’s true. However, as you can see, key geometry numbers — like head tube angle and bottom bracket height — are heavily influenced by suspension travel numbers.

The same can’t be said for other key dimensions like reach and chainstay length. The average reach for a short-travel trail bike in 2026 — those with 130mm of rear suspension travel or less — is less than 5mm shorter than trail bikes with 150mm of rear suspension travel or more. And chainstay lengths are within just 1mm.

As such, looking at either of these dimensions doesn’t tell you much about a bike’s category, that is, whether it’s more “downcountry” or “all-mountain.” Head tube angle and bottom bracket height, on the other hand, do suggest which end of the trail bike spectrum a given bike sits. However, since those are proxies for suspension travel, there’s a strong argument for looking at travel alone to categorize trail bikes.

Of course, for every rule there is an exception. One of those is the Canyon Spectral 125, which, despite speccing a shorter, 140mm fork, has a 64° head tube angle, tied for the most slack among this year’s crop of trail bikes. It’s a bold choice that’s either a clever solution to unlocking this short-travel trail bike’s descending capabilities, or a misstep given the geometry that every other bike brand is using. For most buyers, finding a bike that sticks closely to the “average” geometry numbers shown above will be the safest bet.

To be clear, what gives each trail bike its unique ride feel is the combination of all the geometry numbers. And lest we forget, geometry is about bike fit too. So reach influences comfort on the bike and not necessarily how the bike performs when riding a certain type of trail or at a certain speed. Likewise, chainstay length influences how “playful” or “stable” a bike feels, regardless of whether the bike is downcountry or all-mountain.

The perfect trail bike…

… doesn’t exist. At least, not in the sense that there’s one magic formula that will satisfy every mountain biker. This year’s bike that comes closest to the absolute middle of the trail bike spectrum in terms of travel and geometry is the Giant Trance X 29, so if anything, that might be a good place to start.

I do think we’ll see stabilization and convergence in trail bike geometry over the next few seasons, particularly in head tube angles and bottom bracket heights. That is, assuming trail bikes don’t gain even more suspension travel in the coming years, moving above the consensus 160/150mm front/rear travel range.

What do you think: Is there still room to improve trail bike geometry? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

4 Comments

Jan 10, 2026

One of my favorite builds was short CS, zero drop BB, 65° HTA, 72° STA. Designed more around being behind the bars as opposed to towering over the bars.

With over the counter bikes being in the price range they are, a custom frame is not out of the question. I refer to these as a Prescription frame. One must, absolutely must have their head wrapped around frame lengths and angles for a custom to actually work for them.

Jan 9, 2026

Jan 15, 2026

Jan 11, 2026

That was 8 years ago ...