Over the last three years, how often have you looked out the window as you dressed for a ride and thought “Ugh, is it too smoky to ride?” Probably more times than you’d care to acknowledge. With the new realities of climate change upon us, we now have an additional, fifth season—wildfire season—one that stretches like a dismal umbrella over summer and fall, occasionally crisping the edges of spring and winter to boot. And while the issue of wildfire smoke and its attendant air quality impacts has largely been an issue in the Western US, this past summer has seen smoke from California to the New York Islands.

And in ever more disturbing news, an August 2021 article in the Colorado Sun let us know that “Smoke from faraway wildfires may be worse…than if it came from blazes in their own backyards.” Some studies have shown that long-range smoke may be more toxic and “since one of its characteristics is that its smoky smell disappears, it is sneakier.”

That is, if we don’t see it or smell it, we think we’re okay. Not necessarily. While some smoke is worse than other smoke—think trees burning versus those 387 cans of stuff adorned with skull-and-crossbones in Uncle Joe’s garage (or mine…), the biggest concern is the littlest. PM 2.5—particulate matter 2.5 microns in size (for comparison, a human hair is about 70 microns) — is the major culprit when it comes to bad health outcomes.

The Sun article notes that Colorado Front Range (Colorado Springs to Denver to Ft. Collins area) PM 2.5 peaks are getting bigger, and one of the reasons is long-range wildfire smoke. On August 7, as a result of smoke from California fires, “PM 2.5 particulates on the Front Range […] were measured at 100 micrograms per cubic meter, about three times the daily federal health standard and almost 10 times the amount deemed safe to breathe in on a daily basis over the course of a year.”

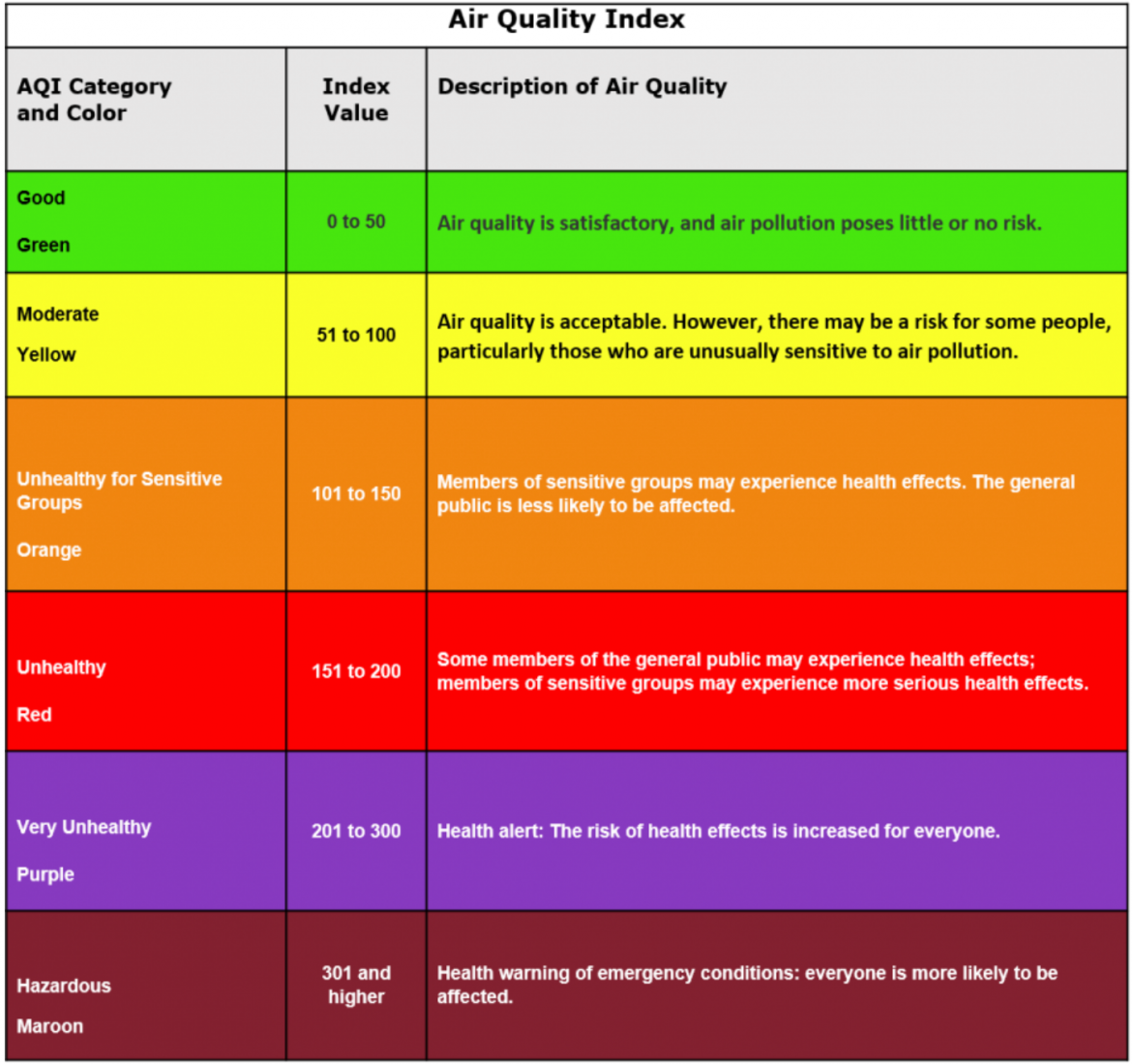

In general, this news makes one want to take up knitting inside of a hermetically sealed chamber with air pumped in from some as-yet unaffected spot on the globe. While there is no absolute rule, no bright red go/no-go line, there are some basic rules of thumb we outdoor exercisers can look to for guidance. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) breaks air quality into six color-coded categories, from green-to-maroon, “good” (0-50) to “hazardous” (301+), and most of us have become hip to this scale.

In speaking with Dr. David Rojas from the Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences department at Colorado State University, he went to great pains to emphasize that the health benefits of exercise far outweigh the risks associated with poor air quality.

“Physical activity activates a positive response from the body which reduces impacts from poor air quality. When we’re below orange—less than 150—and you are healthy, GO OUT! If it’s in the red—more than 150—that’s a grey area, but there are still relatively few days a year when we’re in the red.” Rojas notes that the factors to consider are the concentration of pollutants (measured by the EPA chart) plus the duration of exercise. “Three hours at 100 is safe and is way less of a health risk than sitting on the coach.”

And when the air quality is in that grey zone, peskily hovering between orange and red, the prevailing view appears to indicate that short and intense workouts versus longer and mellower are the way to go, as exposure time to pollutants is reduced.

While there are many ill effects from humans having grown phone-appendages, one positive is that it is now easy to access detailed, fine-grained air quality data for your particular area (the “positive” is that it’s easier to check the “negative.” Oy vey.) The following apps provide real-time info and are popular ways to help determine if it should be indoor yoga with your cat or hill repeats on Strava.

- Purple Air

- AirVisual

- Air Care

- Breezometer

- Virtually any weather app

Each of these — with the exception of Purple Air, which relies on a network of its own air quality monitors — uses data from the EPA. There are of course no hard-and-fast rules for when it’s okay to breathe in smoke. “Never” might be the safest bet, but given our current lot, never is not really an option. Each of us needs to consider our own health status and personal risk factors, our comfort level with those risks, and determine when the benefits of nature, outdoors, and exercise are outweighed by the impacts of orange, red, or maroon air.

But Dr. David Rojas really, really wants you to get on the bike as the long-term health benefits far outweigh the risks of occasional exposure to poor air quality. Additionally, “Substituting the bike for a car trip just one day a week has climate benefits as well as health benefits—a true ‘win-win.’” So in addition to riding vs. driving to the trailhead, why not take the bike to the store/train/work as well? We like riding bikes, and unless an apocalyptic dome of smoke has descended on your specific locale, you’re probably good to go.

Show your Support

Become a Singletracks Pro Supporter today and enjoy benefits like ad-free browsing.

With your support we can provide free worldwide trail information and original content created by our team of independent journalists.

5 Comments

Oct 15, 2021

Oct 16, 2021

Oct 12, 2021

Oct 15, 2021

Oct 16, 2021