If you’ve ever found yourself railing left-hand berms like a pro but fumbling through rights—or vice versa—you’re not alone. Riders frequently mention struggling with corners or switchbacks in one direction more than the other. It’s such a common experience, we had to ask: why?

To find out, I spoke with Dylan Renn, a long-time coach and mountain bike skills instructor with A Singletrack Mind, which offers skills clinics and camps in Oregon and California. His answer? It’s complicated—but not mysterious.

It starts with your lead foot

Almost everyone has a foot they lead with predominantly. It’s the foot that naturally wants to be forward when you’re coasting in a neutral position. And that forward foot can determine how your body behaves in corners.

“In high-speed corners, usually people are better turning towards their forward foot,” says Renn. “So if you have your left foot forward, high-speed corners are usually better for those people to the left.” With our lead foot forward, more weight is on the back foot, which tends to be our stronger side. As a result, “it’s easier to unweight the front foot and have better bike body separation, and the bike leans better.”

The problem becomes apparent when you try to go the other way, ie, a left-foot forward rider cornering to the right. Fluidride founder Simon Lawton explained it this way in a 2019 podcast interview.

“They go into a right-hand turn, they have a tendency to press that right foot by mistake, instead of actually moving to the left foot,” he said. “With very high-level riders — like, very, very high-level riders — they’re so surprised when I show them the weakness in their front foot.”

If you aren’t sure which is your front foot, “stand up and just ride around for a second, sit back down, and then stand up and coast around for a second,” Renn says. Your rearward foot tends to be your stronger, more dominant side. And more often than not, turns toward your forward side are easier compared to turns on your dominant side.

For right-handed riders, the left foot tends to be the lead foot. “We have handedness, like right-handed or left-handed,” Lawton said. “And we have footed-ness, so we have this ability on one side that we maybe don’t possess on the other side.”

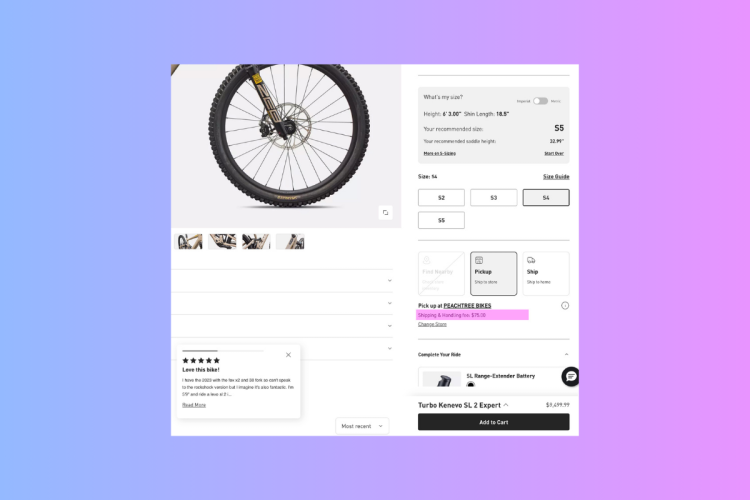

Even your bike knows which side is your better side for cornering. “If you look at your tire, you’ll notice, especially the front tire, […] you’ll see that you wear one side of your tire more than the other,” Renn said. That’s because you’re pushing harder into the turns on your better side, and over time, the additional force adds up.

Climbing switchbacks and jumping are also affected

As most riders know, this left-versus-right imbalance doesn’t just apply to descending. Many of us find it more difficult to climb switchbacks in one direction than the other. In fact, at slower speeds — ie, when climbing — we turn better on the side of our rearward dominant foot. For left-foot forward riders, that means switchbacks to the left are more challenging.

“Most people get caught in a pedal stroke at slow speeds, which then brings their forward foot down and then places weight inside or under the bike,” which makes it harder to turn that direction, Renn says.

Personally, I’ve noticed that I tend to dip my handlebars to the right when jumping, and though this appears to add a little steez, it’s rarely intentional. I asked Renn about this, and he told me it’s likely because my hips aren’t square, which comes back to being a left-foot-forward rider.

“As you release, and you stand up, you’re starting to rotate,” he said. With my left foot forward and right foot back, my right arm is naturally pulled backward, which causes the right side of the bar to dip.

Yes, you can train yourself to turn better in both directions

Fortunately, cornering and climbing imbalance isn’t a life sentence. Renn says he personally corners better to the left—even though he rides right foot forward—because that’s the side he practiced most growing up. “I just made left turns off the side of the road on the way home,” he said. “I did that for years.”

If you want to improve your weak side, Renn suggests intentional practice. “Don’t just do a bunch of drills on your good side,” he says. Practicing figure eights in a parking lot is a good way to get in a lot of turns on both your stronger and weaker sides.

At Fluidride skills clinics, Lawton incorporates drills to help riders improve their corners and turns in both directions. “Immediately, like right off the bat, in the first 10 minutes of class, we’re working on becoming ambidextrous with our lower body.”

Sessioning corners is another way to get better, too. “Make a left turn over and over and over again, and do it at a pace that’s not necessarily at a true high speed, do it at a pace that you can disassemble the movements a little bit so you can be more aware of where your feet, where your hips, where the hands are, where your eyes are.”

Renn also suggests getting comfortable leaning your bike to the left and the right, and returning to the center. Skills instructors call this bike-body separation, and it’s important, especially when cornering. “A lot of people get lost in that. When you hear ‘bike body separation,’ you hear left to right.” Rather, “It’s left to center to right to center. So many people try to separate and just go left to right instead of returning back to center.”

Though it’s natural to have a preferred side when it comes to cornering, and even pro riders struggle, it’s possible to make real progress. “Even though one is going to be significantly more coordinated than the other, you can actually start picking up coordination of what I call ‘your second favorite side,'” Lawton said. “You can start picking up coordination of your second favorite side much more quickly with your lower body than you can with your upper body.”

What about muscle imbalances?

Most people have a dominant hand and, by extension, a stronger, more dominant side of their body. For example, right-handed people tend to have more strength in their right hand because they use it more often, which results in a slight, though noticeable, muscle imbalance.

Mobility is an important factor too, and for some riders, limited mobility can lead to challenges when it comes to cornering. “A lot of people I work with have a hard time creating a body position necessary for a super technical section of trail.” Getting your chest low for climbing switchbacks is key, and if you have a hard time getting your body into that position, you’ll struggle in either direction.

Renn suggests incorporating yoga, stretching, and strength activities to ensure your mobility is good and you don’t have any major imbalances.

Constant improvement

Mountain biking is full of twists and turns for everyone. If you struggle to rail high-speed berms to the right and climb around sharp switchbacks to the left, Renn’s advice is to continue training your body.

“You can always work on it. You can always be better.”

Dylan Renn is a certified mountain bike skills coach through USA Cycling, BICP, Betterride, NICA, NASM. In August his company, A Singletrack Mind, is offering a shuttled skills and camping event at Mt. Hood in Oregon.

2 Comments

Jul 18, 2025

It is all about breaking " instinctive" habits . We see now that some mountain bike coaches don't nip this problem off early , before riders go professional .The bad habit illustrated in this article as "undesireable" can increase the risk of crashes and falls . Sometimes bicycle fitting by people like Neil Stanbury from Australia can help correct this . He has published Youtube videos about offsetting dominance in foot dexterity . The lady I sponsor rode a motorcycle with my riding raceway group and then rode the raceway on her Mondraker Carbon with Rick behind her on his Cannondale . Unusual place to learn but still helpful .

Jul 17, 2025