Editor’s note: Updated with corrections from Shimano.

Some of the first bicycle shifting systems were hand derailed. Riders would dismount at the hill’s crest to loosen their rear axle and move the chain to another gear before descending. Nearly every drivetrain component has improved since then, and there have been some poor choices like adding a second derailleur and extra chainrings. Now we complain about how our 12-speed drivetrains won’t outlast the faithful 8-speed, and whine when there is an occasional mis-shift once every four riding hours. Bicycle drivetrains have come a long way and maybe whining will eventually catch up.

With that front derailleur out of the equation, bike transmissions appear to be relatively simple. The chain clings to a front ring thanks to narrow and wide teeth and tighter tolerances and a well-adjusted derailleur keeps it in place on the cassette while tensioning the chain accordingly. So what are all of those little ramps and divots for on the cassette, and why are some chains directional? We chatted with Nick Murdick from Shimano to learn more.

First up, Shimano uses the shifting language of “inward” and “outward” instead of “lower” and “higher” gears, since the latter two terms are fraught with confusion. Early shifting systems used friction to push the chain in or out across the cassette, relying on friction and pressure alone to make the jump. This worked, but the shifts were often clunky, and the rider sometimes had to decrease pressure on the pedals to allow for a smooth shift that didn’t overstrain the teeth and chain. Another piece of technical info that will be helpful to note is that drivetrain chains don’t pull on all of a cog’s teeth equally. In any gear, more tension is placed on the first couple of teeth at the top of the cassette. Now let’s dig in.

Hyperglide

Shimano’s original Hyperglide (HG) was the first bike drivetrain system designed with the use of a newfangled contraption called a computer. They advertised that fact proudly in the marketing materials. The innovative system aligned the teeth on each of the cogs in a particular orientation so they would catch more quickly once the derailleur was moved in or out. It also created the situation where one roller of the chain could catch on a cog and engage with the newly selected gear before the chain was fully shifted over from the previous cog. This created the sensation of “fast shifting” since the rider could feel a difference before the shift was complete.

Murdick says that “creating shift ramps was really the name of the game. Before that, it was just that some of the teeth were a little bit twisted. The whole idea of shift ramps came with Hyperglide. [There was] a ramp to guide the chain up to the next larger tooth, some teeth that are taller and shorter than others, and really the timing of the teeth so that you could be engaged with two teeth at the same time.”

Hyperglide+

Apparently making those jumps outward, to a smaller cog, is significantly more difficult and that’s what Hyperglide+ (HG+) delivers. The HG+ innovations brought a new shift ramp design. Where original HG had what’s called release-gates to help the chain let go and shift outward, HG+ uses more of a ramp to make a smooth jump.

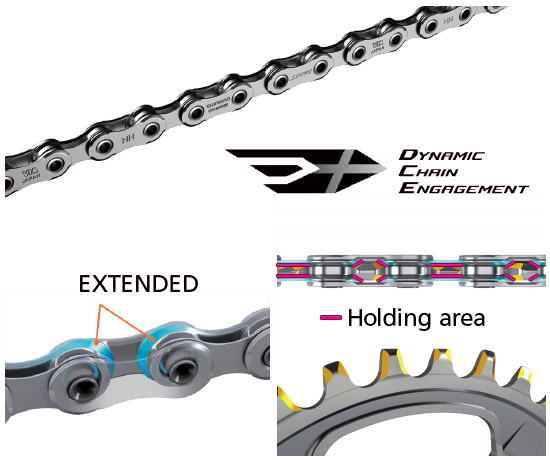

The chain also features an extended inner link plate with HG+ which provided a new tool for better shifting.

“You can imagine that, with inner plates and outer plates, they don’t have the same interface with every tooth of a cog,” says Murdick. “You don’t know which one is going to line up with which one.”

So there was no way to know if an inner or outer link would hit a specific tooth, making it impossible to further dial in the cassette/chain interface. That is, until Hyperglide+ came along. “What that extended inner link plate does is it allows us to almost treat every link like it’s an inner link. So now we have a consistent engagement between the chain and the cogs. So that helps an awful lot.” The new HG+ chain and cassette shapes allowed the chain to be engaged with two cogs at the same time when shifting outward, allowing that shifting direction to be as smooth and immediate as its opposite.

Road vs. mountain chains

Murdick mentioned that the extended inner link plate also helps to straighten the chain out, helping with drivetrain efficiency and chain retention. So the ramped and guided outward shifting improved, coupled with the stiffer chain that also made for better inward shifts. Win/win! Murdick made a comparison to road bikes, stating that “the Dura-Ace chains are designed to wait for the shift gate. In mountain biking, we tend to do a lot more panic shifting. Like ‘I need that gear right now.’ And the [Hyperglide] mountain bike chain will shift whenever you need it to, for faster outward shifting.” For those of you running tiny road cassettes on your downhill bikes, Shimano recommends using their mountain bike chains on Hyperglide systems for faster outward shifts.

Linkglide

Shimano released a new shifting technology last season called Linkglide that we have yet to see on any bikes. It can use any chain and achieves Hyperglide+ style shifting solely by means of ramps and tooth profiles. The chain will wait for a shift gate to move, making it ever so slightly slower. This gives the new system a true longevity focus, as it puts less pressure on both the cassette teeth and chain combined. The new 10- and 11-speed groups are far less expensive than the premium HG+ lineup, and Shimano claims they will be more than three times more durable than the weight-focused Hyperglide+ drivetrains.

Chain skating

Have you ever had a chain drop outward down the cassette when you backpedal? Maybe you’re walking up something steep and the crank spins backward with no pressure on it, then the chain skates toward the smallest cog, which causes the chain to lose tension and rotate off the spinning chainring. Shimano calls this skating.

So annoying. Murdick says, “it’s those release gates that help the chain come down the cassette. When your chain is crossed over [shifted far inward] and you pedal backward, the chain is lined up with those release gates and it wants to come down the cassette.”

“Hardly anyone talks about this, but originally Boost chainline was 53mm, and it got turned into 52mm — almost completely as a direct result of that. It was like ‘okay, 52mm helps prevent the chain from skating down the cassette.’ We can prevent it by changing the tooth profile a little as well.” Murdick mentioned that most of Shimano’s new drivetrains are designed to eliminate skating whenever possible, even on their lower-cost kit. He’s been experimenting with a 55mm chainline on his XC bike, huffing up super steep climbs without issue, so it seems Shimano has this issue largely solved.

The most frustrating place to experience chain skating is while climbing something super steep and rotating your cranks rearward for a split second for better ground clearance. If the chain skates in this instance you’ll be left with a harder gear to mash through while the chain repositions, possibly forcing a dismount.

Chain replacement

Folks often decide to replace a chain based on a measurement between the rollers, as they can begin to wear on the expensive cassette when the steel roller wears thinner and the spaces between them grow. Murdick says that lateral flex in a chain is another factor that can schedule it for replacement. With too much flexibility in the chain it can catch a tooth too early or wiggle to places it’s not supposed to be, causing ghost shifts and dropped chains. If the chain is bad enough the derailleur won’t be able to push it over to the next cog. The amount of float in a derailleur’s upper pulley, the B-gap, and the flex in a chain are all carefully tuned to aid in crisp shifts, and if either wears they need to be replaced.

Unfortunately, there aren’t great ways to know when a chain should be replaced. Murdick says that many of the “trusty” chain-checker tools are often misleading and poorly calibrated. To know if yours is reading chain wear correctly, use it on a new chain to see what it says. Cassettes are wildly expensive, so if your bike isn’t shifting properly and you have already replaced the cable and housing it’s likely time for some fresh links.

If the chain is past its wear-out point, and the cassette is already damaged, a new chain likely won’t shift properly across the worn cogs. In that case, it can be better to continue using the spent chain that’s fully bedded into the cassette until both components are ready for recycling.

That’s enough shift-nerding for one read. Please let us know if you have other drivetrain-related questions we can research in the coming months.