A stream of ideas and passionate personal narratives lit up my inbox after the initial Three Deep Breaths article, and I look forward to covering many of the topics that our readers suggested. To kick things off I want to highlight some ideas from a helpful book that relates directly to the intersection of mental health and mountain biking.

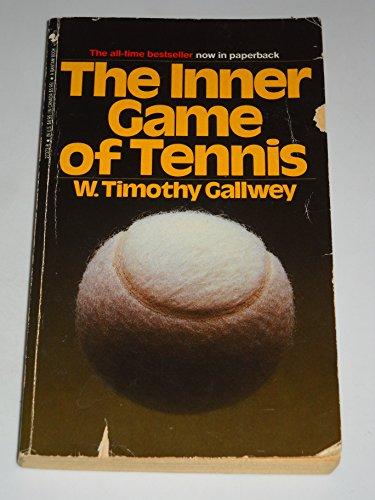

At its most succinct annotation, The Inner Game of Tennis: The Classic Guide to the Mental Side of Peak Performance, by W. Timothy Gallwey, is a thoughtful look at our egos and how to quiet them so that we can enjoy and improve upon the things we love to do. Gallwey is a professional tennis instructor, writer, and teacher. The word “Tennis” in the title can be replaced with mountain biking, painting, crafting, or anything you care to excel at and wish to enjoy fully. Though the book focuses on peak athletic performance, the philosophies Gallwey describes can be applied to any aspect of life that we want to enjoy and be present for. This is the sort of presence that could render our shreds more therapeutic, and quite possibly make them more fun.

One conventional, but outdated philosophy on how to improve our skills at a given activity, and therefore enjoy it more, has been to receive massive amounts of critical feedback on our efforts, then double that feedback with professional instruction on how to improve our methods and efforts. You can see coaches of kids’ sports teams fall into this teaching style occasionally, though it is more often something we as riders do to ourselves. We focus on everything we are doing wrong, watch a few videos about how to do it better, and then continue to chastise ourselves when we can’t mimic the riders’ moves in the video. I have been doing exactly this while trying to learn to manual over the past few seasons. One of Gallwey’s most poetic quotes on human potential illustrates his thesis quite well.

When we plant a rose seed in the earth, we notice that it is small, but we do not criticize it as “rootless and stemless.” We treat it as a seed, giving it the water and nourishment required of a seed. When it first shoots up out of the earth, we don’t condemn it as immature and underdeveloped; nor do we criticize the buds for not being open when they appear. We stand in wonder at the process taking place and give the plant the care it needs at each stage of its development. The rose is a rose from the time it is a seed to the time it dies. Within it, at all times, it contains its whole potential. It seems to be constantly in the process of change; yet at each state, at each moment, it is perfectly all right as it is. -Gallwey

As a professional tennis instructor, Gallwey found that we come to physical activities with two “selves.” First, there is the encourager, teacher, critic, punisher, and fan who is constantly telling us to do something differently or to focus. Then the second self is the doer: a collection of all of the physical experiences and joy we have had in our “flow states,” alongside the brilliance we have witnessed in other talented people. When we silence the scolding and criticism of self one, our second “doer self” can find the flow state and ride in a way that shuts off all of the rest of the world, giving bike rides their deeply therapeutic nature.

In his book on Tennis Gallwey argues that we learn better by letting our subconscious mind focus on what “good play” looks like, then quieting our brains so that our bodies can do their job. Most of us who have been riding for a while have seen skilled riders execute a challenge we are trying to learn or overcome, so we know exactly what it should look like and which techniques make it possible. Knowledge and physical ability are not our barriers; rather our mental game is preventing us from truly believing that we can do something well. In short, the more we force instructions to improve our riding or focus on our past triumphs, the worse our riding ability becomes.

With his students, Gallwey implemented methods of visual demonstration, rather than rote instruction, showing students what well-executed techniques look like and then letting them mimic those movements while playing. The results of this practice were both immediate and measurable, as his students’ ability and enjoyment improved markedly.

For a quick thought experiment, try recalling the last time you were having an “off day” on the bike. Were you focused on the next corner or the last email you sent at work? Were you looking at the landing of the jump, or thinking about the last time you felt great on that same feature? Often times when we can’t find the flow it is because we are judging ourselves, positively or negatively, rather than focusing objectively on the task immediately in front of us.

At roughly 6 minutes and 40 seconds into the video above, professional DH racer Tracey Hannah drops some advice that could come straight out of a book titled “The Inner Game of Mountain Biking.” Hannah tells Paul, the amateur rider in the video to trust his skills, and his bike, and to focus on something else while riding. She suggests paying attention to his breathing or singing a song. Focusing on music or breath can quiet the mind so that the body can do what it knows best. This not only works in the video. I have tried it, and I always enjoy rides more with a good tune rattling between my ears.

The following quote from zen master D.T. Suzuki represents another call into the echo chamber of focus and shreditation. A still mind is ready for performance, while a judging mind is focused on what happened, what “I just did wrong,” or what “was super sick.” As a result, the mind isn’t able to focus on the coming turn or rootball in the path.

Man is a thinking reed but his great works are done when he is not calculating and thinking. ‘Childlikeness’ has to be restored with long years of training in the art of self-forgetfulness. When this is attained, man thinks yet he does not think. He thinks like the showers coming down from the sky; he thinks like the waves rolling on the ocean; he thinks like the stars illuminating the nightly heavens; he thinks like the green foliage shooting forth in the relaxing spring breeze. Indeed, he is the showers, the ocean, the stars, the foliage. –D.T. Suzuki

We can experience more zen shreditation and flow state if we quiet our minds and are free of both positive and negative judgments. While these theories may seem dreamy or unobtainable, they work. Professional athletes of all stripes use a variety of techniques to focus their minds on what is happening in the current moment and surrender themselves to “the zone.”

Have you read any of Gallwey’s books? What do you do to focus more on the ride? Share with us in the comments below.